Introduction

The urge to unravel species distribution processes has increased with the current global crisis, where 15 to 37% of species are expected to face extinction due to climate change (Thomas et al. 2004). This urgency is particularly pertinent for long-lived sessile species like trees, whose range distribution is likely to fail to follow climate change (Zhu, Woodall, and Clark 2012; Sittaro et al. 2017). In an effort to enhance traditional correlative species distribution models (e.g. Guisan and Zimmermann 2000), theory decomposes species distribution into smaller components to develop a more mechanistic, process-based approach (Evans et al. 2016). One such approach is demographic range models, which predicts a species’ distribution based on individual performance governed by growth, survival, and recruitment rates (Pagel and Schurr 2012). This approach operates under the hypothesis that population growth rate (\(\lambda\)), determined by demographic rates, varies across the environment, with the species range limit defined by conditions where \(\lambda\) is positive (Maguire Jr 1973; Holt 2009; Pang et al. 2024).

By approaching species distributions from a demographic perspective, we can better capture the complexity of forest dynamics arising from environmental variation and species interactions (Schurr et al. 2012; Svenning et al. 2014). Several studies have attempted to predict species distributions based on demographic performance of forest trees. The simplest implementations of these approaches rely on environment-dependent demographic rates to estimate \(\lambda\) (e.g. Merow et al. 2014; Csergő et al. 2017). However, competition is a fundamental determinant of demographic rates (Luo and Chen 2011; Clark et al. 2011; Zhang, Huang, and He 2015) and population performance (Scherrer et al. 2020; Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021) in forest ecosystems. Incorporating competition is therefore particularly important given the projected risk of community reshuffling under global change (Alexander et al. 2016). This more complete, realized expression of the niche (Hutchinson 1957) may help explain why North American forest trees often fail to occupy their full climatically suitable ranges (Boucher-Lalonde, Morin, and Currie 2012; Talluto et al. 2017).

An increasing body of evidence challenges theoretical expectations by observing weak correlations between tree demographic performance and species distributions (McGill 2012; Thuiller et al. 2014; Csergő et al. 2017; Bohner and Diez 2020; Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021; Midolo, Wellstein, and Faurby 2021; Guyennon et al. 2023). This mismatch is often attributed to the oversight of processes beyond climate and competition. For instance, habitat availability coupled with dispersal limitation can constrain species distributions even in areas where local demographic performance is positive (Pulliam 2000). However, the methodological approaches used to quantify demographic performance are rarely challenged, perhaps because studies rely on diverse and non-comparable frameworks. Some analyses infer performance based solely on one of the growth, survival, or recruitment rates (McGill 2012; Bohner and Diez 2020). Even when demographic rates are combined within population models, key components such as recruitment, are often excluded due to data limitations (Kunstler et al. 2021; Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021). Furthermore, density dependence is sometimes ignored altogether (Csergő et al. 2017; Ohse et al. 2023), and when included, studies rarely distinguish between conspecific and heterospecific competition (Bohner and Diez 2020; Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021). Finally, despite increasing recognition of the importance of propagating model and data uncertainty (Milner-Gulland and Shea 2017; Malchow and Hartig 2024), most of these studies evaluate performance under average environmental conditions and rely on pointwise estimates, thereby overlooking the uncertainty associated with demographic responses.

Rather than asking whether demographic performance correlates with species distributions, a more fruitful question may be how climate and competition jointly shape demographic performance. Despite substantial progress, we still lack a comprehensive partitioning of the sensitivity of forest dynamics to local and biogeographical drivers (Ohse et al. 2023). For instance, Clark et al. (2011) found that annual growth was more sensitive to competition, whereas fecundity responded more strongly to climate. In contrast, Copenhaver-Parry and Cannon (2016) reported growth to be more sensitive to climate than to competition. Although these studies provide important insights into how forest trees may respond to climate change and management, they focus on individual demographic components rather than their integrated effects on population growth. This limitation is particularly important if sensitivity to climate and competition varies across life-history stages (Russell et al. 2012; Ettinger and HilleRisLambers 2013). Moreover, the sensitivity of \(\lambda\) to climate and competition may depend on a species’ position within its range, such as climate may exert stronger control under abiotic stress, whereas competition may dominate under more benign conditions (Louthan, Doak, and Angert 2015). Nevertheless, such range-dependent partitioning of sensitivity remains largely unexplored for forest trees (Ohse et al. 2023).

Here, we evaluate how climate and competition jointly shape the demography and population growth rate of the 31 most abundant forest tree species across eastern North America (Figure 1). Leveraging the full latitudinal extent of forest inventories (26 - 53°) across the United States and Canada, we capture the entire geographic ranges of these species. We model growth, survival, and recruitment as functions of temperature, precipitation, and conspecific and heterospecific basal area (as proxies for competition), and integrate these climate- and competition-dependent vital rates into size-structured Integral Projection Models (IPMs) to estimate population growth rate (\(\lambda\)).

Our primary goal is to quantify how sensitive \(\lambda\) is to climate and competition across species’ ranges. Using perturbation analysis (Caswell 2000), we decompose the contribution of each covariate to variation in \(\lambda\) under the specific environmental and competitive conditions experienced across plot-years. This approach allows us to evaluate the overall sensitivity of \(\lambda\) to a given covariate while explicitly accounting for the inherent variability experienced by the species across its range. For instance, even if a species is highly sensitive to temperature, its average population response may be weak if most populations occur under near-optimal conditions. Finally, expanding on previous evidence that North American trees have shown limited cold-edge expansion and hot-edge contraction under climate change (Talluto et al. 2017), we test whether sensitivity to climate and competition varies across species’ geographic ranges. By quantifying the relative effects of climate and competition on population growth rates, our framework offers a mechanistic basis for understanding how forest tree may respond to climate change, management, and conservation actions.

Methods

Perturbation analysis

To understand how climate and competition affect forest population dynamics, we developed species-specific, Integral Projection Models (IPM) parameterized with climate- and competition-dependent demographic rates (described in the following section). Deriving population growth rate (\(\lambda\)) from the IPM, we used perturbation analysis to assess the sensitivity of \(\lambda\) to competition and climate conditions (Caswell 2000). We define sensitivity as the partial derivative of \(\lambda\) with respect to a covariate \(X\), which can take the form of either conspecific or heterospecific density dependence competition, or temperature or precipitation climate conditions. In practice, we quantify sensitivity by slightly increasing each covariate value \(X_j\) to \(X_j^{'}\) and computing the change in \(\lambda\) following the right-hand part of Equation 1:

\[ \frac{\partial \lambda_{ij}}{\partial X_j} \bigg\rvert_{K_{ij}} \approx \frac{\Delta \lambda_{ij}}{\Delta X_j} = \frac{|f(X_j^{'}) - f(X_j)|}{X_j^{'} - X_j} \](1)

Sensitivity is evaluated separately for each species \(i\) and is conditional on the specific climate and competition conditions observed for the plot-year \(j\), along with the Kernel \(K_{ij}\) parameters. We set the perturbation size to a 1% increase in the normalized scale for each covariate. For instance, a 1% increase translates to a rise of 0.3°C for Mean Annual Temperature (MAT) and 26 mm for Mean Annual Precipitation (MAP). Because the competition metric is computed at the individual level, the perturbation was applied to each individual before computing the plot basal area (BA), where a 1% increase corresponds approximately to a rise of 1.2 cm in dbh. As we were interested in the absolute difference, the resulting sensitivity value ranges between 0 and infinity, with lower values indicating a lower sensitivity of \(\lambda\) to the specific covariate. Specifically, sensitivity (\(S\)) to competition or climate of species \(i\) for a given plot-year \(j\) is defined as follows:

\[ \begin{split} &S_{comp, ij} = \frac{\partial \lambda_{ij}}{\partial BA_{cons, i}} + \frac{\partial \lambda_{ij}}{\partial BA_{het, i}} \\[2pt] &S_{clim, ij} = \frac{\partial \lambda_{ij}}{\partial MAT_{i}} + \frac{\partial \lambda_{ij}}{\partial MAP_{i}} \\[2pt] \end{split} \](2)

When averaging \(S_{X,i}\) across \(j\), this metric reflects the sensitivity of \(\lambda_i\) to \(X\), which is conditional upon the probability distribution of the covariate \(X\). We categorized each plot into cold, center, or hot conditions along the MAT axis for every species. Plots were labeled as cold (or hot) if the average MAT fell below (above) the 10% (90%) probability distribution, with all intermediate plots considered center plots. Thus, sensitivity to a covariate in the cold range of the species means the average sensitivity among all plots classified as cold. It is important to note that this classification is also conditional on the probability distribution of observed MAT within the species.

Model

To assess the population growth rate of the 31 tree species, we developed a Bayesian Mechanistic Model. This pars a process dynamic model (IPM) with data sub-models for each vital rate to formally quantify process and parameter uncertainity. An IPM is a mathematical tool used to represent the dynamics of structured populations and communities. It distinguishes itself from traditional population models with the representation of a continuous trait in discrete time (Easterling, Ellner, and Dixon 2000). This is especially relevant for trees due to the considerable variability in demographic rates depending on individual size (Kohyama 1992). Specifically, the IPM consists of a set of functions predicting the transition of a distribution of individual traits from time \(t\) to time \(t+\Delta t\), where \(\Delta t\) represents the number of discrete year intervals:

\[ n(z', t + \Delta t) = \int_{L}^{U} \, K(z', z, \theta)\, n(z, t)\, \mathrm{d}z \](3)

The continuous trait \(z\) at time \(t\) represents the diameter at breast height (DBH), bouded between the lower (\(L\)) and upper (\(U\)) values, and \(n(z, t)\) characterizes the continuous DBH distribution for a population. The probability of the population distribution size from \(n(z, t)\) to \(n(z', t + \Delta t)\) is governed by the kernel \(K\) and the species-specific parameters \(\theta\). The kernel \(K\), a continuous version of the discretized projection Matrix in structured population models, is composed of three sub-models:

\[ K(z', z, \theta) = [Growth(z', z, \theta) \times Survival(z, \theta)] + Recruitment(z, \theta) \](4)

The growth function describes how individual trees increase in DBH, while the survival function determines the probability of staying alive throughout the next time step. The recruitment model describes the number of individuals ingressing the population. These three models are independent and do not share any parameters. Below, we describe the basic (intercept) version of these models, followed by the inclusion of climate and competition covariate in each of them.

Demographic rates

Growth - the size in DBH of an individual at time \(t + \Delta t\) after growing from time \(t\) is determined by:

\[ dbh_{i,t + \Delta t} \sim N(\mu_{i, t+\Delta t}, \sigma) \](5)

We used the von Bertalanffy growth equation to describe the annual growth rate in DBH of an individual \(i\) (Von Bertalanffy 1957). The average size at time \(t+\Delta t\) from the initial size \(dbh_{i, t}\) of an individual at time \(t\) is given by:

\[ \mu_{i, t+\Delta t} = dbh_{i,t} \times e^{-\Gamma \Delta t} + \zeta_{\infty} (1- e^{-\Gamma \Delta t}) \](6)

Where \(\Delta t\) is the time interval between the initial and final size measurements and \(\Gamma\) represents a dimensionless growth rate coefficient. \(\zeta_{\infty}\) denotes the asymptotic size, which is the location at which growth approximates to zero. The rationale behind this model is that the growth rate exponentially decreases with size, converging to zero as size approaches \(\zeta_{\infty}\). This assumption is particularly valuable in the context of the IPM, as it prevents eviction — where individuals are projected beyond the limits of the size distribution (\([L, U]\)) defined by the Kernel.

Survival - The chance of a mortality event (\(M\)) for an individual \(i\) within the time interval between \(t\) and \(t+\Delta t\) is modeled as a Bernoulli distribution:

\[ M_i \sim Bernoulli(p_i) \](7)

Here, \(M_i\) represents the individual’s status (alive/dead) and \(p_i\) the mortality probability of the individual \(i\). The mortality probability is calculated based on the annual survival rate (\(\psi\)) and the time interval between census (\(\Delta t\)):

\[ p_i = 1 - \psi^{\Delta t} \](8)

The model assumes that the survival probability (\(1 - p_i\)) increases with the longevity parameter \(\psi\), but is compensated exponentially with the increase in time \(\Delta t\).

Recruitment - We combined data from the U.S. and Quebec forest inventories to obtain a broader range of climatic conditions. However, these inventories have inconsistent protocols for recording seedlings, saplings, and juveniles. Most of all, they have different size thresholds for individual-based measurements. Therefore, we quantified the recruitment rate (\(I\)) as the ingrowth of new individuals into the adult population, defined as those with a DBH exceeding 12.7 cm. The quantity \(I\) encompasses the processes of fecundity, dispersal, growth, and survival up to reaching the size threshold. Similar to growth and survival, the count of ingrowth individuals (\(I\)) reaching the 12.7 cm size threshold depends on the time interval between measurements. We introduce two parameters to control the potential number of recruited individuals: \(\phi\), determining the annual ingrowth rate per square meter, and \(\rho\), denoting the annual survival probability of each ingrowth individual:

\[ I \sim Poisson(~\phi \times A \times \frac{1 - \rho^{\Delta t}}{1-\rho}~) \](9)

Where \(A\) represents the area of the plot in square meters. The model assumes that new individuals enter the population annually at a rate of \(\phi\), and their likelihood of surviving until the subsequent measurement (\(\rho\)) declines over time. Note that \(\rho\) in Equation 9 is not associated with Equation 8 determining the survival of the adults. Instead, \(\rho\) is estimated from the data of individuals arriving in the population. Once an individual is recruited into the population, a submodel determines its initial size \(z_I\), increasing linearly with time:

\[ z_{I} \sim TNormal(\Omega + \beta \Delta t,~\sigma, ~ \alpha, ~ \beta) \](10)

The \(TNormal\) is a truncated distribution with lower and upper limits determined by the \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) parameters, respectively. We set \(\alpha\) to 12.7 cm, aligning it with the ingrowth threshold, while \(\beta\) is set to infinity to allow for an unbounded upper limit.

Covariates

Random effects - We introduced plot-level random effects in each of the growth, survival, and recruitment demographic component to account for shared variance between the individuals within the same plot. For a demographic component with an average intercept \(\overline{I}\), an offset value (\(\alpha\)) is drawn for each plot \(j\) from a normal distribution with a mean of zero and variance \(\sigma\):

\[ \begin{split} &\alpha_{j} \sim N(0, \sigma) \\[2pt] &I_j = \overline{I} + \alpha_j \end{split} \](11)

Where \(\sigma\) represents the variance among all plots \(j\) and \(I\) can take one of three forms: \(\Gamma\) for growth, \(\psi\) for survival, and \(\phi\) for the recruitment model.

Competition - We used basal area of larger individuals (BAL; asymmetric competition) instead of total basal area (BA; symmetric competition), assuming that competition for light is the primary competitive factor driving forest dynamics (Pacala et al. 1996). Therefore, each of the growth (\(\Gamma\)), longevity (\(\psi\)), and recruitment survival (\(\rho\)) parameters decreases exponentially with BAL. Take \(I\) as one of the three parameters, the effect of BAL on \(I\) is driven by two parameters describing the conspecific (\(\beta\)) and heterospecific (\(\theta\)) competition:

\[ I + \beta (BAL_{cons} + \theta \times BAL_{het}) \](12)

When \(\theta < 1\), conspecific competition is stronger than heterospecific competition. Conversely, heterospecific competition prevails when \(\theta > 1\), and when \(\theta = 1\), there is no distinction between conspecific and heterospecific competition. Note that \(\beta\) is also unbounded, allowing it to converge towards negative (indicating competition) or positive (indicating facilitation) values. Furthermore, we fixed \(\theta = 1\) for the recruitment (\(I = \rho\)) due to model convergence issues. The recruitment model also accounts for the conspecific density dependence effect on the annual ingrowth rate (\(\phi\)). Specifically, \(\phi\) increases with \(BAL_{cons}\) as a positive effect of seed source up to reach the optimal density of recruitment, \(\delta\), where it then decreases with more conspecific density due to competition at a rate proportional to \(\sigma\):

\[ \phi + \left(\frac{BAL_{cons} - \delta}{\sigma}\right)^2 \](13)

Climate - We selected mean annual temperature and mean annual precipitation bioclimatic variables as they are widely used in species distribution modeling and were previously found relevant to model demography of these species (Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021). Each demographic component \(I\), representing either \(\Gamma\) for growth, \(\psi\) for longevity, or \(\phi\) for ingrowth, varies as a bell-shaped curve determined by an optimal climate condition (\(\xi\)) and a climate breadth parameter (\(\sigma\)):

\[ I + \left(\frac{MAT - \xi_{MAT}}{\sigma_{MAT}}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{MAP - \xi_{MAP}}{\sigma_{MAP}}\right)^2 \](14)

The climate breadth parameter (\(\sigma\)) influences the strength of the specific climate variable’s effect on each demographic component. This unimodal function is flexible, assuming various shapes, such as bell, quasi-linear, or flat shapes. However, this flexibility introduces the possibility of parameter degeneracy or redundancy, where different combinations of parameter values yield similar outcomes. To address this issue, we constrained the optimal climate condition parameter (\(\xi\)) within the observed climate range for the species, assuming that the optimal climate condition falls within our observed data range.

Forest inventory and climate data

We used two open inventory datasets from eastern North America: the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) dataset in the United States (O’Connell et al. 2007) and the Forest Inventory of Québec (Minist‘ere des Ressources Naturelles 2016). At the plot level, we focused on plots sampled at least twice, excluding those that had undergone harvesting to concentrate solely on natural dynamics. Specifically, we selected surveys conducted for the FIA dataset using the modern standardized methodology implemented since 1999. After applying these filters, our final dataset encompassed nearly 26,000 plots spanning a latitude range from 26° to 53° (Figure S7). Each plot within the dataset was measured between 1970 and 2021, with observation frequencies ranging from 2 to 7 times and an average of 3 measurements per plot. The time intervals between measurements varied from 1 to 40 years, with a median interval of 7 years (Figure S7).

These datasets provide individual-level information on the DBH and the status (dead or alive) of more than 200 species. From this pool, we selected the 31 most abundant species (Table S1). This selection comprises 9 conifer species and 22 hardwood species. We ensured an even distribution of species across the shade tolerance axis, with three species classified as very intolerant, nine as intolerant, eight as intermediate, eight as tolerant, and five as very tolerant (Burns, Honkala, and Others 1990).

For the competition metric, we use asymmetric competition for light, meaning that each individual is affected only by neighbour individuals of larger size. We quantified asymmetric competition for light for a focal individual in a given plot by summing the total basal area of all individuals larger than the focal one, herein BAL. We further split BAL into the total density of conspecific and heterospecific individuals. For the climate variable, we obtained the 19 bioclimatic variables with a 10 \(km^2\) (300 arcsec) resolution grid, covering the period from 1970 to 2018. These climate variables were modeled using the ANUSPLIN interpolation method (McKenney et al. 2011). We used each plot’s latitude and longitude coordinates to extract the MAT and MAP climate variables. In cases where plots did not fall within a valid pixel of the climate variable grid, we interpolated the climate condition using the eight neighboring cells. Due to the transitional nature of the dataset, we considered both the average and standard deviation of MAT and MAP over the years within each time interval.

Model fit and validation

We fitted each of the growth, survival, and recruitment models separately for each species, using the Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) algorithm implemented in the Stan software (version 2.30.1 Team and Others 2022) with the cmdstandr R package interface (version 0.5.3 Gabry, Češnovar, and Johnson 2023). We conducted 2000 iterations for the warm-up and 2000 iterations for the sampling phase for each of the four chains, resulting in 8000 posterior samples (excluding the warm-up). However, we kept only the last 1000 iterations of the sampling phase to save computation time and storage space, resulting in 4000 posterior samples. We build and fit each demographic component incrementally, from a simple intercept, and gradually incorporate plot random effects, competition, and climate covariates. Recall that our goal is not to have the most complex model to achieve the highest predictive metric but to make inferences (Tredennick et al. 2021). We focus on assessing the relative effects of climate and competition while controlling for other influential factors. Therefore, our modeling approach is guided by biological mechanisms, which tend to provide more robust extrapolation (Briscoe et al. 2019) rather than being solely dictated by specific statistical metrics. Nevertheless, we checked if increasing model complexity with new covariates does not result in worse performance using complementary metrics such as mean squared error (MSE), pseudo \(R^2\) (Gelman et al. 2019), and Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOO-CV). Detailed discussions regarding model fit, diagnostics, and model comparison can be found in supplementary material 1.

With the fitted demographic components, we constructed the Kernel \(K\) of the IPM following Equation 4. We employed the mid-point rule to perform the discrete-form integration of the continuous \(K\) (Ellner, Childs, and Rees 2016). This involved discretizing the projection kernel \(K\) using bins of 0.1 cm, which are considered appropriate for obtaining unbiased estimates for trees (Zuidema et al. 2010). Finally, we computed the asymptotic population growth rate (\(\lambda\)) using the leading eigenvalue of the discretized matrix \(K\). The code to fit each demographic component is available in the TreesDemography GitHub repository. The code for the IPM model and the respective sensitivity analysis is available in the forest-IPM GitHub repository.

Results

Model validation

All species-specific demographic components demonstrated convergence with \(\hat{R} <1.05\) and low to no divergent iterations. In comparing the simple intercept model with the more complete versions, the LOO-CV consistently favored the complete model for all three demographic rates, featuring plot random effects, competition, and climate covariates, over other competing models (supplementary material 1). The absolute values of LOO-CV suggested that the growth model gained the most information from including covariates, followed by recruitment and survival models. We further validated our model predictions by comparing the parameters with traits groups such as growth rate classes, maximum observed size, maximum observed age, shade tolerance, and seed mass (Burns, Honkala, and Others 1990; Díaz et al. 2022).

The growth model intercept comprises two parameters, one determining the asymptotic size (\(\zeta_{\infty}\)) and the annual growth rate \(\Gamma\). The \(\zeta_{\infty}\) can be interpreted as the maximum predicted size of the species, which correlates well across all 31 species with the maximum observed size in the literature (\(R^2 = 0.31\), Figure 2). Similarly, \(\Gamma\) among the species exhibited a distribution aligning with the fast, moderate, and slow-growing traits (Figure S8). In the survival model, the expected longevity (\(L\)) can be derived from the annual survival rate ( \(\psi\)) following the equality \(L = e^{\psi}\), showing a high correlation with the maximum observed age in the literature (\(R^2 = 0.59\), Figure 2). In the recruitment model, the log of the annual ingrowth rate (\(\phi\)) reduced linearly with seed mass (Figure S9), capturing the seed mass-growth rate tradeoff (Reich et al. 1998). Additionally, the annual survival probability of ingrowth (\(\rho\)) decreased with intolerance to shade (Figure S10).

Both conspecific and heterospecific competition effects for the growth and survival models increased with intolerance to shade (Figure 3). The stronger competition effect of conspecific over heterospecific was consistent for almost all species in both growth and survival models. Only two species for growth and three for survival among the 31 presented stronger heterospecific competition than conspecific competition. Moreover, Fagus grandifolia and Thuja occidentalis exhibited positive density dependence for the survival model. For recruitment, the effect of total stand density increased with shade intolerance among the species (Figure S11).

The distribution of optimal MAT (\(\xi_{MAT}\)) and MAP (\(\xi_{MAP}\)) for the 31 species revealed that the optimal climates for growth, survival, and recruitment were rarely located at the center of the species ranges (Figure S12 and S13). Furthermore, most species exhibited some degree of demographic compensation, that is, opposing responses to the environment between demographic rates (Villellas et al. 2015). Lastly, the climate breadth (\(\sigma\)) determined how flat or narrow the performance of species was across MAT and MAP. We found among all species that climate breadth increased with range size, demonstrating that species with more range occupancy had larger niche breadths (Figure S14). The exception was the niche breadth of survival over MAT, showing a weak, flat correlation.

\(\lambda\) sensitivity to climate and competition

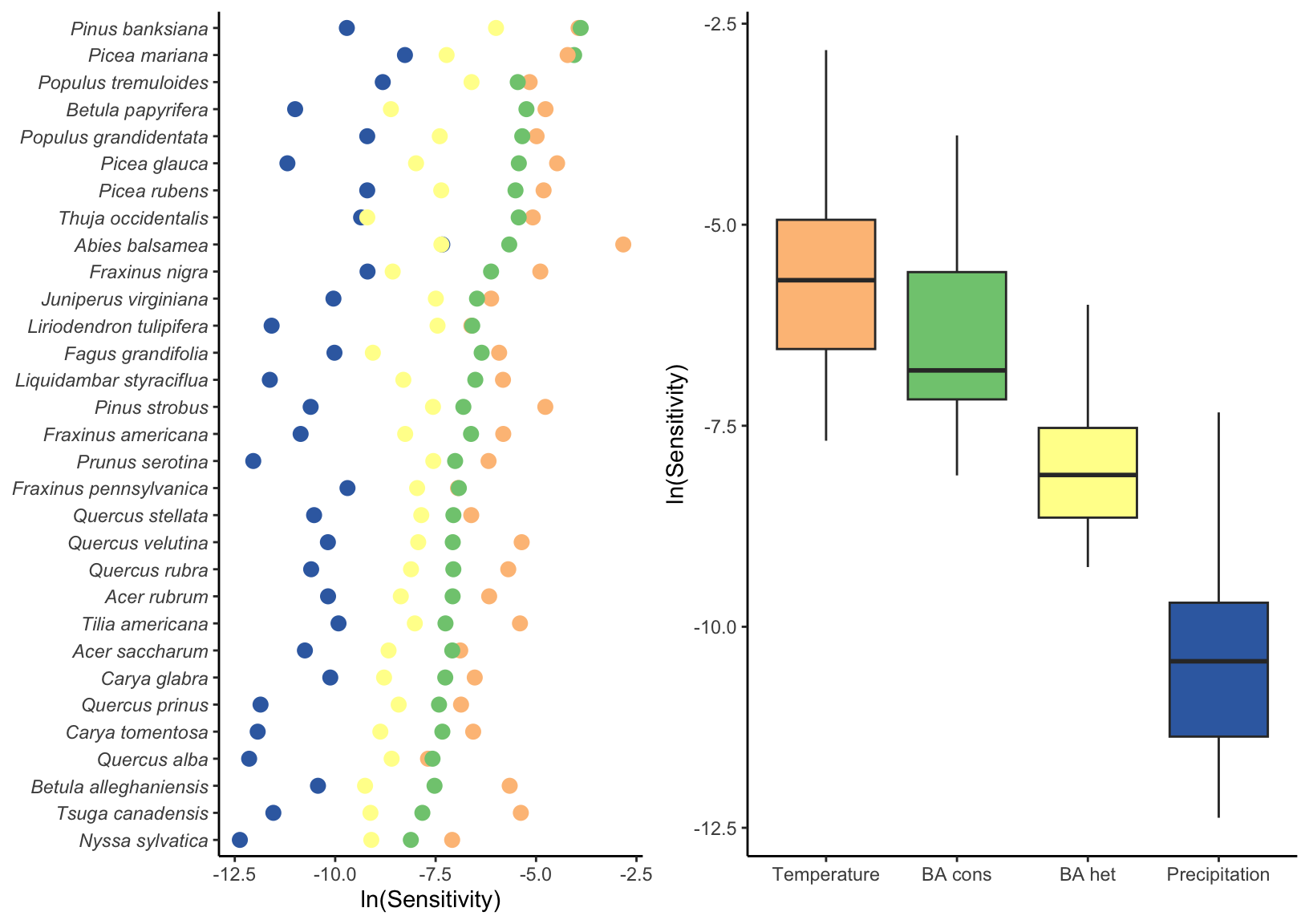

We used perturbation analysis to assess the relative contribution of each covariate to changes in \(\lambda\). Figure 4 describes the sensitivity of each species’ population growth rate to conspecific and heterospecific competition, temperature, and precipitation averaged across all plot-year observations. Across all species, \(\lambda\) exhibited higher sensitivity to temperature, followed by conspecific and heterospecific competition, while sensitivity to mean annual precipitation was practically zero. This observation of sensitivity to the covariates was consistent across all species.

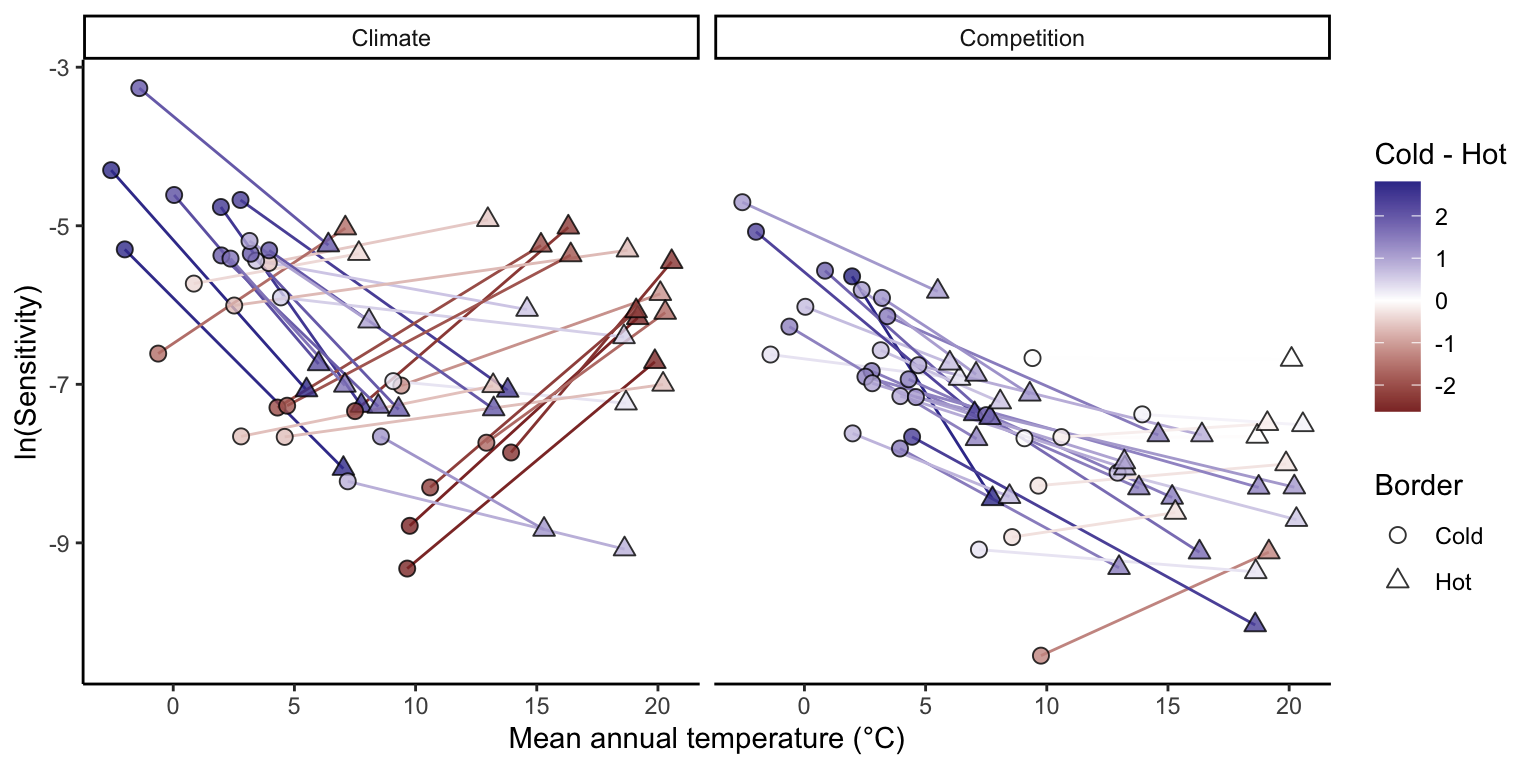

We divided plots into cold and hot regions of each species’ range based on the MAT to test whether sensitivity to climate and competition differs between range margins (Figure 5). Most species distributed in colder climates showed a decrease in climate sensitivity from the cold to the hot range margin. In contrast, species whose distributions are centered in warmer climates tended to exhibit higher climate sensitivity at the hot margin than at the cold margin. Sensitivity to competition was generally higher at the cold margin than at the hot margin for most species, regardless of their overall distribution. This elevated sensitivity to competition at the cold margin was particularly pronounced for boreal species.

We next examined how the relative importance of climate versus competition for population growth varies

We further included sensitivity estimates at the center of each species’ distribution to characterize the shape of sensitivity changes across the range (Figure S15). Overall, most species exhibited a near linear change in sensitivity to both climate and competition from the cold to the hot range margins. For climate sensitivity, three of the four species displaying a concave pattern (i.e. sensitivity was higher at both range edges than at the center) were among those with the largest geographic ranges. In contrast, for competition, four species showed a convex pattern, with sensitivity to competition peaking at the center of the distribution relative to the range edges. These four species also exhibited the highest overall sensitivity to competition and were all predominantly distributed in colder climates.

We then examined how the relative importance of climate versus competition for population growth varies across species’ thermal range positions (Figure 6). For most species, \(\lambda\) was consistently more sensitive to climate than to competition across cold, center, and hot range positions. Across the MAT gradient, the relative influence of climate increased toward both the cold and hot range margins. This pattern indicates that species occurring at the extremes of their thermal distributions are more strongly climate-sensitive than those located near the center of their ranges. Notably, the mechanisms underlying this increase differed between cold and hot range margins (Figure S16). At the cold margin, sensitivities to both climate and competition increased, but the proportional increase was larger for climate. In contrast, at the hot margin, the greater relative importance of climate resulted primarily from a decline in sensitivity to competition.

Discussion

We developed an integral projection model for 31 tree species linking growth, survival, and recruitment to stand level \(\lambda\) in order to assess the sensitivity of \(\lambda\) to climate and competition. Our model advances previous analysis of tree species performance by (i) explicitly incorporating climate and competition effects in the recruitment model, (ii) distinguishing between conspecific and heterospecific competition, while (iii) tracking model’s uncertainty at both the individual and plot levels. Moreover, we designed a modular approach that is easily extendable to include any of the over 200 available species in the dataset and additional covariates influencing each demographic rate.

The results reveal that, for all species, adding climate and competition covariates enhances the predictability of all demographic components in comparison to a simple random effect model without covariates. Nevertheless, the most influential variable remained the local plot conditions captured by the random effects. Therefore, we evaluated species sensitivity to climate and competition while considering plot-level variability. Across the species and their respective ranges, we found that \(\lambda\) was more sensitive to temperature and conspecific basal area of larger individuals. Furthermore, these sensitivities were contingent on the range position of the species, with climate being relatively more important than competition at both the cold and hot range border. These findings contribute to a better understanding of how tree species might respond to novel conditions arising from climate change and perturbations, providing valuable insights for their management.

Fit of demographic components

Our model demonstrated remarkable coherence when reproducing the known variation in traits related to growth, survival, and recruitment components found in the literature. The intercepts for growth and survival were correlated with maximal size and longevity (Burns, Honkala, and Others 1990), while the recruitment intercept aligned well with the seed mass (Díaz et al. 2022). Additionally, the models effectively reproduced the fast-slow continuum (Salguero-G’omez et al. 2016), showing a negative correlation between growth and survival rate and a positive correlation between growth and recruitment rate (Figure S17). Regarding competition, the model captured the negative correlation between density dependence and shade tolerance. The model also matches a common expectation of communities where species coexist, with a stronger response to conspecific competition relative to heterospecific competition, crucial for biodiversity maintenance (Chesson 2000). The intensity of conspecific density dependence was also higher for fast-growing trees than for slow-growing ones (Figure S18), similar to observations in tropical trees (Zhu et al. 2018). For climate, validation is challenging due to limited data on optimal temperature and precipitation measures. Nevertheless, our results align with others, indicating the presence of demographic compensation across forest trees (Bohner and Diez 2020; Yang et al. 2022). Furthermore, the estimated breadth of response to climate correlates with the range size (Figure S14), suggesting that the model captures information not explicitly included.

Most of the variability in \(\lambda\) was associated with local plot conditions captured by random effects, consistent with previous studies (Vanderwel et al. 2016; Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021; Itter and Finley 2024). This pattern suggests that demographic variation is influenced by drivers beyond the climatic and competitive factors explicitly modeled here. At local scales, for instance, soil nitrogen availability (Ib’añez et al. 2018) and mixed mycorrhizal associations (Luo et al. 2023) can enhance tree growth rates. At broader spatial scales, disturbances such as wildfires and insect outbreaks play fundamental roles in shaping forest dynamics and stand structure (Franklin et al. 2002), causing synchronized mortality and altering species composition and abundance. Similarly, three Pinus species across the United States exhibited structured spatial variation in mortality driven primarily by local disturbance agents rather than broad climatic gradients (Bauman, McMahon, and Johnson 2025). Although our analyses focused on quantifying the effects of climate and competition, other covariates may contribute more strongly to variation in demographic rates. For instance, tree growth models show improved predictive performance when incorporating extreme climatic events (Sangin’es de C’arcer et al. 2017), and drought extremes, rather than mean precipitation, were the strongest predictors of fecundity after temperature in several species (Clark et al. 2011).

\(\lambda\) sensitivity to climate and competition

We found across all species that the sensitivity of \(\lambda\) was highest for temperature, followed by conspecific competition. Previous studies assessing the relative effects of climate and competition on tree performance have reported contrasting results. For example, some studies suggest that competition exerts a stronger influence on growth than climate (G’omez-Aparicio et al. 2011; Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021), whereas others report the opposite pattern (Copenhaver-Parry and Cannon 2016). Moreover, the relative importance of climate and competition can vary across demographic components, with growth often being more sensitive to competition and fecundity more sensitive to climate (Clark et al. 2011). Indeed, five dominant tree species in Poland showed high sensitivity to climate, with fecundity declining under warming temperatures (Foest et al. 2025).

These contrasting findings may partly arise because sensitivity is frequently evaluated for individual demographic rates rather than for their integrated effect on population growth. This is particularly critical since \(\lambda\) does not respond equally to all demographic components. Our additional sensitivity analyses revealed that \(\lambda\) was most responsive to recruitment, followed by survival, with a comparatively smaller contribution from growth (see Supplementary Material 3). Given that recruitment tends to be more sensitive to temperature (Clark et al. 2011; Foest et al. 2025), this greater elasticity of \(\lambda\) to recruitment may explain why population growth rate is overall more sensitive to climate than to competition.

Assessing climate sensitivity across the species range distribution revealed divergent responses. As species’ performance responds nonlinearly to climate, lower sensitivity values to a climate covariate indicate that the species operates under optimal climate conditions, whereas higher sensitivity values suggest the species is deviating from its optimal climate condition. Overall, climate sensitivity (primarily driven by MAT) was higher at both the cold and hot range extremes. This implies that species coming from colder temperatures exhibit optimal performance towards their warmer range, and vice versa for species from hotter conditions. Interestingly, the demographic components driving higher sensitivity to climate at the cold and hot extremes differ. The recruitment and growth models primarily influenced sensitivity at the cold border, while the survival and recruitment models dominated at the hot border, specially at high competition conditions (see Figure S22). Previous studies have indicated climate-constrained growth rates at the cold border for North American (Ettinger and HilleRisLambers 2013) and European (Kunstler et al. 2021) trees. Consistent with our results, a decrease in survival at the hot border was observed for European trees (Kunstler et al. 2021), though not in eastern North America (Purves 2009).

The sensitivity of \(\lambda\) to competition increased almost linearly toward colder temperatures for most species. Due to the nonlinearity between species’ performance and competition, the sensitivity of \(\lambda\) to changes in competition decreases as stand density increases (negative exponential shape). This implies that the observed decrease in sensitivity to competition toward the hot range results from an overall increase in stand density (i.e. competition intensity). Indeed, biotic interactions are often more critical at the warm range border (Paquette and Hargreaves 2021). However, when evaluating only the growth rate of North American (Ettinger and HilleRisLambers 2013) and European (Kunstler et al. 2011) trees, the effect of competition remains constant across the climate range.

Limitations and Future Perspectives

Structured population models, such as the IPM, play a crucial role in capturing ontogenetic variability within tree population dynamics. While the growth model inherently considers individual size, the survival and recruitment models are size-independent. We attempted to incorporate the widely assumed “U-shape” form of mortality rate changes with individual size (Lines, Coomes, and Purves 2010), but it performed worse than the simple random effects one (Figure S6). Mortality has been observed to increase with individual size (Luo and Chen 2011; Hember, Kurz, and Coops 2017), but its significance appears to manifest only when interacting with climate and competition (Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021). The challenge in capturing size dependence in the survival model likely stems from the lack of information on small individuals (dbh < 12.7 cm) and the rarity of larger individuals in datasets, even for extensive forest inventories (Canham and Murphy 2017). Despite not explicitly including individual size in the survival model, its indirect influence is included with the asymmetric competition, where smaller individuals experience higher competitive pressure. Another limitation of this model, shared with many models using forest inventory data (Kunstler2021; Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021; Guyennon et al. 2023), is its focus on adults, while tree fecundity can be influenced by climate (Clark et al. 2021), and the dynamics of recruitment may not necessarily align with those of adults (Serra-Diaz et al. 2016; Wason and Dovciak 2017; but see Canham and Murphy 2016).

The modular nature of our approach makes it easily extensible to include new species or covariates. For instance, additional covariates such as water balance or evapotranspiration could be tested to evaluate the impact of drought-induced mortality (Peng et al. 2011). Furthermore, exploring the interaction between climate, competition, and individual size can enhance predictions of demographic rates (Peng et al. 2011; Ford et al. 2017; Rollinson, Kaye, and Canham 2016; Le Squin, Boulangeat, and Gravel 2021). An overlooked but computationally expensive improvement involves jointly fitting the growth, survival, and recruitment models to explore their interdependency (Pang et al. 2024). This would enable leveraging ecological knowledge, such as life history tradeoffs, by sharing information between processes with abundant data (e.g. growth) and those with scarce data (e.g. recruitment). Future steps should focus on better understanding the variability captured by random effects and translating it into ecological processes. While we addressed individual and plot-level model uncertainty, further considerations for other sources of variability arising from temporal stochasticity in climate and competition covariates are essential. This will enhance our understanding of the effects of spatiotemporal variability on species performance across their range (Holt, Barfield, and Peniston 2022).

References

Alexander, Jake M., Jeffrey M. Diez, Simon P. Hart, and Jonathan M. Levine. 2016. “When Climate Reshuffles Competitors: A Call for Experimental Macroecology.” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 31 (11): 831–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.08.003.

Bauman, David, Sean M McMahon, and Daniel J Johnson. 2025. “Mosaic of Size-Dependent Mortality in Three Ecologically and Economically Important Pine Species Reveals Patterns Across Space and Time.” Global Ecology and Biogeography 34 (10): e70141.

Bohner, Teresa, and Jeffrey Diez. 2020. “Extensive mismatches between species distributions and performance and their relationship to functional traits.” Ecology Letters 23 (1): 33–44.

Boucher-Lalonde, V’eronique, Antoine Morin, and David J. Currie. 2012. “How are tree species distributed in climatic space? A simple and general pattern.” Global Ecology and Biogeography 21 (12): 1157–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2012.00764.x.

Briscoe, Natalie J., Jane Elith, Roberto Salguero-G’omez, Jos’e J. Lahoz-Monfort, James S. Camac, Katherine M. Giljohann, Matthew H. Holden, et al. 2019. “Forecasting species range dynamics with process-explicit models: matching methods to applications.” Ecology Letters 22 (11): 1940–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13348.

Burns, Russell M, Barbara H Honkala, and Others. 1990. “Silvics of North America: 1. Conifers; 2. Hardwoods Agriculture Handbook 654.” US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, DC.

Canham, Charles D., and Lora Murphy. 2016. “The demography of tree species response to climate: Seedling recruitment and survival.” Ecosphere 7 (8): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1424.

———. 2017. “The demography of tree species response to climate: Sapling and canopy tree survival.” Ecosphere 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1701.

Caswell, Hal. 2000. Matrix population models. Vol. 1. Sinauer Sunderland, MA.

Chesson, Peter. 2000. “Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity.” Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst 31: 343–66. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.343.

Clark, James S., Robert Andrus, Melaine Aubry-Kientz, Yves Bergeron, Michal Bogdziewicz, Don C. Bragg, Dale Brockway, et al. 2021. “Continent-wide tree fecundity driven by indirect climate effects.” Nature Communications 12 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20836-3.

Clark, James S., David M. Bell, Michelle H. Hersh, and Lauren Nichols. 2011. “Climate change vulnerability of forest biodiversity: Climate and competition tracking of demographic rates.” Global Change Biology 17 (5): 1834–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02380.x.

Copenhaver-Parry, Paige E., and Ellie Cannon. 2016. “The relative influences of climate and competition on tree growth along montane ecotones in the Rocky Mountains.” Oecologia 182 (1): 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-016-3565-x.

Csergő, Anna M., Roberto Salguero-G’omez, Olivier Broennimann, Shaun R. Coutts, Antoine Guisan, Amy L. Angert, Erik Welk, et al. 2017. “Less favourable climates constrain demographic strategies in plants.” https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12794.

Díaz, Sandra, Jens Kattge, Johannes H C Cornelissen, Ian J Wright, Sandra Lavorel, St’ephane Dray, Björn Reu, et al. 2022. “The global spectrum of plant form and function: enhanced species-level trait dataset.” Scientific Data 9 (1): 755.

Easterling, Michael R., Stephen P. Ellner, and Philip M. Dixon. 2000. “Size-specific sensitivity: applying a new structured population model.” Ecology 81 (3): 694–708. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[0694:SSSAAN]2.0.CO;2.

Ellner, Stephen P, Dylan Z Childs, and Mark Rees. 2016. Data-driven modelling of structured populations. Springer.

Ettinger, Ailene K., and Janneke HilleRisLambers. 2013. “Climate isn’t everything: Competitive interactions and variation by life stage will also affect range shifts in a warming world.” American Journal of Botany 100 (7): 1344–55. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1200489.

Evans, Margaret E K, Cory Merow, Sydne Record, Sean M. McMahon, and Brian J. Enquist. 2016. “Towards Process-based Range Modeling of Many Species.” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 31 (11): 860–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.08.005.

Foest, Jessie Josepha, Jakub Szymkowiak, Marcin Dyderski, Dave Kelly, Georges Kunstler, Szymon Jastrzębowski, and Michał Bogdziewicz. 2025. “Forest Fecundity Declines as Climate Shifts.”

Ford, Kevin R., Ian K. Breckheimer, Jerry F. Franklin, James A. Freund, Steve J. Kroiss, Andrew J. Larson, Elinore J. Theobald, and Janneke HilleRisLambers. 2017. “Competition alters tree growth responses to climate at individual and stand scales.” Canadian Journal of Forest Research 47 (1): 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2016-0188.

Franklin, Jerry F., Thomas A. Spies, Robert Van Pelt, Andrew B. Carey, Dale A. Thornburgh, Dean Rae Berg, David B. Lindenmayer, et al. 2002. “Disturbances and structural development of natural forest ecosystems with silvicultural implications, using Douglas-fir forests as an example.” Forest Ecology and Management 155 (1-3): 399–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00575-8.

Gabry, Jonah, Rok Češnovar, and Andrew Johnson. 2023. cmdstanr: R Interface to ’CmdStan’.

Gelman, Andrew, Ben Goodrich, Jonah Gabry, and Aki Vehtari. 2019. “R-squared for Bayesian Regression Models.” American Statistician 73 (3): 307–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2018.1549100.

G’omez-Aparicio, Lorena, Ra’ul García-Vald’es, Paloma Ruíz-Benito, and Miguel A. Zavala. 2011. “Disentangling the relative importance of climate, size and competition on tree growth in Iberian forests: Implications for forest management under global change.” Global Change Biology 17 (7): 2400–2414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02421.x.

Guisan, Antoine, and Niklaus E. Zimmermann. 2000. “Predictive habitat distribution models in ecology.” Ecological Modelling 135 (2-3): 147–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(00)00354-9.

Guyennon, Arnaud, Björn Reineking, Roberto Salguero-Gomez, Jonas Dahlgren, Aleksi Lehtonen, Sophia Ratcliffe, Paloma Ruiz-Benito, Miguel A Zavala, and Georges Kunstler. 2023. “Beyond mean fitness: Demographic stochasticity and resilience matter at tree species climatic edges.” Global Ecology and Biogeography 32 (4): 573–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13640.

Hember, Robbie A., Werner A. Kurz, and Nicholas C. Coops. 2017. “Relationships between individual-tree mortality and water-balance variables indicate positive trends in water stress-induced tree mortality across North America.” Global Change Biology 23 (4): 1691–1710. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13428.

Holt, Robert D. 2009. “Bringing the Hutchinsonian niche into the 21st century: Ecological and evolutionary perspectives.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (Supplement 2): 19659–65. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905137106.

Holt, Robert D., Michael Barfield, and James H. Peniston. 2022. “Temporal variation may have diverse impacts on range limits.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 377 (1848). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0016.

Hutchinson, G Evelyn. 1957. “Concluding remarks.” In Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology, 22:415–27.

Ib’añez, In’es, Donald R. Zak, Andrew J. Burton, and Kurt S. Pregitzer. 2018. “Anthropogenic nitrogen deposition ameliorates the decline in tree growth caused by a drier climate.” Ecology, January. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2095.

Itter, Malcolm, and Andrew O Finley. 2024. “Making More with Forest Inventory Data: Toward a Scalable, Dynamical Model of Forest Change.” bioRxiv, 2024–07.

Kohyama, Takashi. 1992. “Size-structured multi-species model of rain forest trees.” Functional Ecology, 206–12.

Kunstler, Georges, C’ecile H. Albert, Benoît Courbaud, S’ebastien Lavergne, Wilfried Thuiller, Ghislain Vieilledent, Niklaus E. Zimmermann, and David A. Coomes. 2011. “Effects of competition on tree radial-growth vary in importance but not in intensity along climatic gradients.” Journal of Ecology 99 (1): 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01751.x.

Kunstler, Georges, Arnaud Guyennon, Sophia Ratcliffe, Nadja Rüger, Paloma Ruiz-Benito, Dylan Z. Childs, Jonas Dahlgren, et al. 2021. “Demographic performance of European tree species at their hot and cold climatic edges.” Journal of Ecology 109 (2): 1041–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13533.

Le Squin, Amaël, Isabelle Boulangeat, and Dominique Gravel. 2021. “Climate-induced variation in the demography of 14 tree species is not sufficient to explain their distribution in eastern North America.” Global Ecology and Biogeography 30 (2): 352–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13209.

Lines, Emily R., David A. Coomes, and Drew W. Purves. 2010. “Influences of forest structure, climate and species composition on tree mortality across the Eastern US.” PLoS ONE 5 (10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013212.

Louthan, Allison M., Daniel F. Doak, and Amy L. Angert. 2015. “Where and When do Species Interactions Set Range Limits?” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 30 (12): 780–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.011.

Luo, Shan, Richard P. Phillips, Insu Jo, Songlin Fei, Jingjing Liang, Bernhard Schmid, and Nico Eisenhauer. 2023. “Higher productivity in forests with mixed mycorrhizal strategies.” Nature Communications 14 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36888-0.

Luo, Yong, and Han Y H Chen. 2011. “Competition, species interaction and ageing control tree mortality in boreal forests.” Journal of Ecology 99 (6): 1470–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2011.01882.x.

Maguire Jr, Bassett. 1973. “Niche response structure and the analytical potentials of its relationship to the habitat.” The American Naturalist 107 (954): 213–46.

Malchow, Anne-Kathleen, and Florian Hartig. 2024. “Calibration, Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis of Ecological Models—a Review.” Vol. In Revision). Authorea.

McGill, Brian J. 2012. “Trees are rarely most abundant where they grow best.” Journal of Plant Ecology 5 (1): 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtr036.

McKenney, Daniel W., Michael F. Hutchinson, Pia Papadopol, Kevin Lawrence, John Pedlar, Kathy Campbell, Ewa Milewska, Ron F. Hopkinson, David Price, and Tim Owen. 2011. “Customized Spatial Climate Models for North America.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 92 (12): 1611–22. https://doi.org/10.1175/2011BAMS3132.1.

Merow, Cory, Andrew M. Latimer, Adam M. Wilson, Sean M. Mcmahon, Anthony G. Rebelo, and John A. Silander. 2014. “On using integral projection models to generate demographically driven predictions of species’ distributions: Development and validation using sparse data.” Ecography 37 (12): 1167–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.00839.

Midolo, Gabriele, Camilla Wellstein, and Søren Faurby. 2021. “Individual fitness is decoupled from coarse-scale probability of occurrence in North American trees.” Ecography 44 (5): 789–801. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.05446.

Milner-Gulland, E. J., and K. Shea. 2017. “Embracing uncertainty in applied ecology.” Journal of Applied Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12887.

Minist‘ere des Ressources Naturelles. 2016. “Norme d’inventaire ecoforestier: placettes-echantillons temporaires.” Direction des inventaires forestier, Ministère des Ressources naturelles,Québec.

O’Connell, M B, E B LaPoint, J A Turner, T Ridley, D Boyer, A Wilson, K L Waddell, and B L Conkling. 2007. “The forest inventory and analysis database: Database description and users forest inventory and analysis program.” US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

Ohse, Bettina, Aldo Compagnoni, Caroline E. Farrior, Sean M. McMahon, Roberto Salguero-G’omez, Nadja Rüger, and Tiffany M. Knight. 2023. “Demographic synthesis for global tree species conservation.” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 38 (6): 579–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2023.01.013.

Pacala, Stephen W., Charles D. Canham, John Saponara, John A. Silander, Richard K. Kobe, Eric Ribbens, John A Silander Jr., Richard K. Kobe, and Eric Ribbens. 1996. “Forest models defined by Field Measurements: Estimation, Error Analysis and Dynamics.” Ecological Monographs 66 (1): 1–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/2963479.

Pagel, Jörn, and Frank M. Schurr. 2012. “Forecasting species ranges by statistical estimation of ecological niches and spatial population dynamics.” Global Ecology and Biogeography 21 (2): 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00663.x.

Pang, Sean Eng Howe, Erola Fenollosa, Cory Merow, Antoine Guisan, Jens-Christian Svenning, and Roberto Salguero-Gómez. 2024. “From Niche Theory to Demographic Realities: The Demographic Niche Concept for Understanding Range-Wide Population Dynamics.” Authorea. Under Revision in Ecography. Doi 10.

Paquette, Alexandra, and Anna L Hargreaves. 2021. “Biotic interactions are more often important at species’ warm versus cool range edges.” Ecology Letters 24 (11): 2427–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13864.

Peng, Changhui, Zhihai Ma, Xiangdong Lei, Qiuan Zhu, Huai Chen, Weifeng Wang, Shirong Liu, Weizhong Li, Xiuqin Fang, and Xiaolu Zhou. 2011. “A drought-induced pervasive increase in tree mortality across Canada’s boreal forests.” Nature Climate Change 1 (9): 467–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1293.

Pulliam, H. Ronald. 2000. “On the relationship between niche and distribution.” Ecology Letters 3 (4): 349–61. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2000.00143.x.

Purves, Drew W. 2009. “The demography of range boundaries versus range cores in eastern US tree species.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 276 (1661): 1477–84. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.1241.

Reich, P. B., M. G. Tjoelker, M. B. Walters, D. W. Vanderklein, and C. Buschena. 1998. “Close association of RGR, leaf and root morphology, seed mass and shade tolerance in seedlings of nine boreal tree species grown in high and low light.” Functional Ecology 12 (3): 327–38. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00208.x.

Rollinson, Christine R., Margot W. Kaye, and Charles D. Canham. 2016. “Interspecific variation in growth responses to climate and competition of five eastern tree species.” Ecology 97 (4): 1003–11. https://doi.org/10.1890/15-1549.1.

Russell, Bayden D., Christopher D. G. Harley, Thomas Wernberg, Nova Mieszkowska, Stephen Widdicombe, Jason M. Hall-Spencer, and Sean D. Connell. 2012. “Predicting ecosystem shifts requires new approaches that integrate the effects of climate change across entire systems.” Biology Letters 8 (2): 164–66. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2011.0779.

Salguero-G’omez, Roberto, Owen R Jones, Eelke Jongejans, Simon P Blomberg, David J Hodgson, Cyril Mbeau-Ache, Pieter A Zuidema, Hans De Kroon, and Yvonne M Buckley. 2016. “Fast–slow continuum and reproductive strategies structure plant life-history variation worldwide.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (1): 230–35. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1506215112.

Sangin’es de C’arcer, Paula, Yann Vitasse, Josep Peñuelas, Vincent E. J. Jassey, Alexandre Buttler, and Constant Signarbieux. 2017. “Vapor-pressure deficit and extreme climatic variables limit tree growth.” Global Change Biology 12 (10): 3218–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13973.

Scherrer, Daniel, Yann Vitasse, Antoine Guisan, Thomas Wohlgemuth, and Heike Lischke. 2020. “Competition and demography rather than dispersal limitation slow down upward shifts of trees’ upper elevation limits in the Alps.” Journal of Ecology, no. March: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13451.

Schurr, Frank M., Jörn Pagel, Juliano Sarmento Cabral, Jürgen Groeneveld, Olga Bykova, Robert B. O’Hara, Florian Hartig, et al. 2012. “How to understand species’ niches and range dynamics: A demographic research agenda for biogeography.” Journal of Biogeography 39 (12): 2146–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2012.02737.x.

Serra-Diaz, Josep M., Janet Franklin, Whalen W. Dillon, Alexandra D. Syphard, Frank W. Davis, and Ross K. Meentemeyer. 2016. “California forests show early indications of both range shifts and local persistence under climate change.” Global Ecology and Biogeography 25 (2): 164–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12396.

Sittaro, Fabian, Alain Paquette, Christian Messier, and Charles A. Nock. 2017. “Tree range expansion in eastern North America fails to keep pace with climate warming at northern range limits.” Global Change Biology, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13622.

Svenning, Jens-Christian Christian, Dominique Gravel, Robert D Holt, Frank M Schurr, Wilfried Thuiller, Tamara Münkemüller, Katja H Schiffers, et al. 2014. “The influence of interspecific interactions on species range expansion rates.” Ecography 37 (October 2013): 1198–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.00574.x.

Talluto, Matthew V., Isabelle Boulangeat, Steve Vissault, Wilfried Thuiller, and Dominique Gravel. 2017. “Extinction debt and colonization credit delay range shifts of eastern North American trees.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 1 (June): 0182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0182.

Team, Stan Development, and Others. 2022. “Stan modeling language users guide and reference manual, version 2.30.1.” Stan Development Team.

Thomas, Chris D, Alison Cameron, Rhys E Green, Michel Bakkenes, Linda J Beaumont, Yvonne C Collingham, Barend F N Erasmus, et al. 2004. “Extinction risk from climate change.” Nature 427 (6970): 145–48.

Thuiller, Wilfried, Tamara Munkemuller, Katja H Schiffers, Damien Georges, Stefan Dullinger, Vincent M Eckhart, Thomas C Edwards, et al. 2014. “Does probability of occurrence relate to population dynamics?” Ecography 37 (12): 1155–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.00836.

Tredennick, Andrew T, Giles Hooker, Stephen P Ellner, and Peter B Adler. 2021. “A practical guide to selecting models for exploration, inference, and prediction in ecology.” Ecology 102 (6): e03336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3336.

Vanderwel, Mark C., Hongcheng Zeng, John P. Caspersen, Georges Kunstler, and Jeremy W. Lichstein. 2016. “Demographic controls of aboveground forest biomass across North America.” Ecology Letters 19 (4): 414–23. https://doi.org/pb.

Villellas, Jes’us, Daniel F. Doak, María B. García, and William F. Morris. 2015. “Demographic compensation among populations: What is it, how does it arise and what are its implications?” Ecology Letters 18 (11): 1139–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12505.

Von Bertalanffy, Ludwig. 1957. “Quantitative laws in metabolism and growth.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 32 (3): 217–31.

Wason, Jay W., and Martin Dovciak. 2017. “Tree demography suggests multiple directions and drivers for species range shifts in mountains of Northeastern United States.” Global Change Biology 23 (8): 3335–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13584.

Yang, Xianyu, Amy L. Angert, Pieter A. Zuidema, Fangliang He, Shongming Huang, Shouzhong Li, Shou Li Li, Nathalie I. Chardon, and Jian Zhang. 2022. “The role of demographic compensation in stabilising marginal tree populations in North America.” Ecology Letters 25 (7): 1676–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14028.

Zhang, Jian, Shongming Huang, and Fangliang He. 2015. “Half-century evidence from western Canada shows forest dynamics are primarily driven by competition followed by climate.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (13): 4009–14. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1420844112.

Zhu, Kai, Christopher W. Woodall, and James S. Clark. 2012. “Failure to migrate: Lack of tree range expansion in response to climate change.” Global Change Biology 18 (3): 1042–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02571.x.

Zhu, Y., S. A. Queenborough, R. Condit, S. P. Hubbell, K. P. Ma, and L. S. Comita. 2018. “Density-dependent survival varies with species life-history strategy in a tropical forest.” Ecology Letters. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12915.

Zuidema, Pieter A, Eelke Jongejans, Pham D Chien, Heinjo J During, and Feike Schieving. 2010. “Integral projection models for trees: a new parameterization method and a validation of model output.” Journal of Ecology 98 (2): 345–55.